A detailed report on the treatment plan at the Charité Women’s Clinic.

Endometriosis is one of the most common abdominal diseases in women. Roughly every 10th woman suffers from the symptoms, and it often takes years. Until then, many women try to somehow cope with their pain. They believe that even the most severe pain is normal and part of the menstrual period. In order to find ways to deal with the symptoms or to start therapy, it is important to get to know your own body and its reactions. Good information and working with experienced, supportive doctors. In order to give you a better insight into the therapy, we have put together this article for you.

Specially trained gynecological experts work at our endometriosis center. Knowledge and expertise on this complex disease are bundled here. There is close cooperation between different medical disciplines.

In Germany, it takes an average of six years from the appearance of the first symptoms to the diagnosis of endometriosis. The reasons for this unnecessarily long path of suffering are usually a lack of knowledge and experience with this disease. This is exactly where the idea of a certified endometriosis center comes in: Here, patients are cared for and treated by specially trained experts. In this way, knowledge and competence are bundled and used for the benefit of the patients. The collaboration between the

medical disciplines is practiced daily.

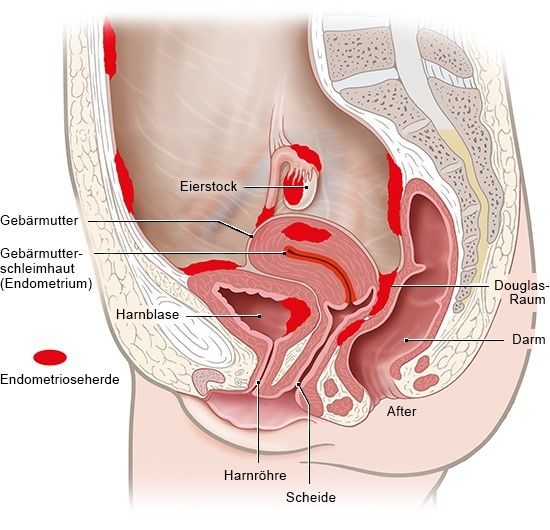

Endometriosis is one of the most common abdominal diseases in women. The cause is the accumulation of uterine lining outside the uterus. Experts also refer to such tissue islands as “endometriosis foci”. They can happen without a woman noticing. For others, however, endometriosis is a chronic condition that causes severe pain and lowers fertility. It often takes years before endometriosis is identified as the cause of the symptoms. Until the diagnosis is made, many women try to somehow manage their pain. They believe that even the most severe pain is normal and part of the menstrual period.

So far, endometriosis cannot be completely cured — but there are various ways to treat the symptoms. If the therapy is tailored to the personal circumstances and the severity of the disease, many women can live quite well with endometriosis.

As with other chronic diseases, it is important to get to know your own body and its reactions in order to find ways to deal with the symptoms. Good information and working with experienced, supportive doctors can help.

Symptoms

The main symptom of endometriosis is abdominal pain. They often occur with the menstrual period, during or after intercourse. The pain can sometimes be stronger, sometimes weaker and radiate into the lower abdomen, back and legs. They are often experienced as cramping and can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

How the pain is expressed also depends on where the uterine lining has settled in the abdominal cavity. For example, foci of endometriosis can grow on the outside of the uterus or in the wall of a fallopian tube. Often the ovaries, the “Douglas space” between the uterus and rectum and the associated connective tissue are also affected. When the ovaries or fallopian tubes are affected, fertility is often impaired.

Sometimes foci of endometriosis also form in organs such as the bladder or intestines, which can lead to problems with urination and bowel movements. Severe endometriosis can severely reduce quality of life and performance.

To give you a better impression of the treatment options, we have created a chronological overview of a possible treatment plan for you in the following section. A typical endometriosis therapy in our endometriosis center (level III) looks like this:

1. First presentation

Now it’s on, your first appointment in our endometriosis center. Perhaps you were lucky and your doctor advised you early on that your symptoms could be related to endometriosis. Perhaps you felt like many other fellow sufferers and it cost you years and many visits to the doctor before the word endometriosis was used for the first time.

The aim of the first appointment, the so-called first presentation, is first and foremost a detailed survey of your medical history (anamnesis). In order to optimally prepare for the visit, we ask you to fill out our anamnesis sheet in advance. This helps you not to forget crucial facts in the excitement of the doctor’s talk. It will help your doctor to fully understand and document your symptoms (symptoms).

In a personal conversation, the results of the anamnesis sheet will be summarized with you and it will be worked out which complaints are in the foreground. Not only your pain and bleeding problems play a role here, but also, for example, digestive problems, whether you want to start a family in the near future and how much you or your partnership are burdened by your symptoms.

With your consent, your doctor will then carry out a detailed physical examination. You probably already know a lot from your regular examinations at the gynecologist. Nonetheless, an examination for suspected endometriosis is a little more detailed:

At the beginning, a so-called mirror adjustment (speculum examination) is carried out. It is possible to inspect the entire external genitalia (vulva) and the vagina. In particular, the cervix (portio) and the posterior vaginal vault must be examined carefully, since endometrial foci may already be identified.

Next, a palpation exam is performed. The doctor inserts one or two fingers one after the other into the vagina. Endometrial foci on the cervix or between the vagina and rectum, which can be felt as painful indurations or nodules, are often noticed here. You can also feel the position and mobility of the uterus and possibly cysts on the ovary by additionally touching the abdominal wall with the other hand (bimanual palpation examination). You can also judge whether your pelvic floor muscles are already very tense due to your symptoms. At the end of the palpation examination, a finger is also inserted into the rectum (rectal examination) while another finger remains in the vagina. This is particularly important in order to palpate possible endometrial foci with bowel involvement. Unfortunately, these are still often undetected, which is why we attach great importance to this part of the investigation. Even if a rectal exam sounds embarrassing or uncomfortable at first, your doctor will help you relax and you will see that this part of the exam is nowhere near as uncomfortable as you thought.

The palpation examination is followed by an ultrasound examination. Because it is much easier to assess, the ultrasound head should be inserted through the vagina (transvaginally). Each examiner has his own scheme, which helps to assess all organs in sequence and not to forget any. A look at the urinary bladder already allows one to conclude whether it is affected by endometriosis. It should also be assessed in each case whether endometrial foci can be seen between the vagina and rectum or whether there are otherwise indications of intestinal involvement. An assessment should be made of whether the uterus can move to the bladder and bowel or whether there is already evidence of adhesions. The examiner will also take a close look at the uterus itself — the ultrasound can often detect endometriosis of the uterus (adenomyosis or adenomyosis uteri). The ovaries are also thoroughly inspected. If there are so-called endometriomas (endometriosis cysts on the ovary) in this area, this can be easily recognized with the ultrasound. If you have dealt with endometriosis a bit, you may already know that endometriosis foci are often on the peritoneum. These foci can usually not be seen in the ultrasound. All other typical localizations, on the other hand, can be assessed with ultrasound Very young women in particular are increasingly finding their way to us for consultation hours. If you have not had sexual intercourse before, a transvaginal ultrasound is often not possible.

Many doctors then do what is known as an abdominal ultrasound. With this method, however, an assessment of the organs as described above is only possible with difficulty. In this case, we therefore recommend an ultrasound from the intestine. That sounds uncomfortable at first (the doctor is of course aware of this), but you can use it to assess the organs just as well as with an ultrasound from the vagina.

A kidney sound may be performed after the transvaginal examination. If the previous examination revealed indications of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with involvement of the ureters, your doctor must rule out that there is already an obstruction of the urine. Urinary congestion does not cause any discomfort at the beginning and so it can progress unnoticed until the kidney may no longer function properly. Fortunately, that’s rarely the case with endometriosis.

After the anamnesis and the examination, the findings are summarized and the likelihood of the diagnosis of endometriosis is discussed. To make the diagnosis of endometriosis, from our point of view, no conclusive surgery with a tissue examination is necessary. A trained doctor can make the diagnosis with a high degree of certainty based on the medical history and examination results.

At the latest after the diagnosis has been made, the time has come to explain what endometriosis actually is, how it develops, which therapy options are available and which steps are sensible for you at the current time. This depends largely on your complaints, your examination results and your current life situation. At the end of your first appointment, you and your doctor will determine a treatment plan that will meet your needs and your individual situation.

Endometriosis is a chronic disease and although we can now do a lot to alleviate or even eliminate symptoms, we cannot (yet) cure it. This means that endometriosis will likely be with you for as long as you are menstruating. In addition, every step of therapy will require your cooperation — regardless of whether you regularly take a hormone preparation, an operation is planned and / or you are dealing with endometriosis with the help of a multimodal pain therapy concept. Because of this, it is important that you have a good understanding of this condition. We would like to help you on this path and on the one hand explain the next steps to you using the treatment plan on your personal path and on the other hand answer and clarify general questions using the guide.

Our tip: Write down all your questions now!

Further diagnostics

Sometimes further diagnostic measures are useful in order to assess the spread of the endometriosis even more precisely and to be able to plan the further procedure reliably.

This can include the following examinations:

● Sigmoidoscopy with endosonography (examination of the rectum)

This is a special type of colonoscopy in which a flexible tube with a special ultrasound head at the tip is inserted into the intestine in order to be able to assess the wall layers of the intestine with regard to endometriosis ingrowth. With the combined rectoscopy, in which one can also assess the innermost layer of the intestinal wall using a camera integrated in the tube, any constrictions can also be assessed.

● Colonoscopy (complete colonoscopy)

In a classic colonoscopy, a flexible tube is also inserted into the intestine. In contrast to endosonography, this has an integrated camera and can therefore only assess the intestinal mucosa, i.e. the innermost layer of the intestine, from the inside. However, endometriosis ingrowth into the interior of the intestine is very rare and can usually only be detected during the bleeding. This examination alone is therefore rarely helpful in diagnosing endometriosis. In individual cases it is nevertheless useful to be able to discover high-lying intestinal sections and possible constrictions caused by endometriosis.

The latest devices have an endoscope with an integrated camera and ultrasound head, so that endosonography and colonoscopy can be combined. Of course, all examinations are not dangerous and help us a lot to better understand your illness.

● Kidney scintigraphy

With a kidney scintigraphy, the functionality of both kidneys can be clarified. This should be considered if the ultrasound scan shows a kidney congestion. In contrast to the blood tests, a separate analysis of the kidney function is possible. You do not have to be fasting for a kidney scintigraphy, you should in particular ensure that you drink enough fluids. Water is best here. If you lie quietly for at least 30 minutes, a slightly radioactive substance is applied to you via a flexule (indwelling vein catheter), which is first distributed in the body and then excreted via the kidneys. lie quietly, a slightly radioactive substance is applied to you via a flexula (indwelling vein catheter), which is first distributed in the body and then excreted via the kidneys. A special camera will take pictures of you for at least 30 minutes and can thus trace the path of the radioactive substance in your body and analyze the amount excreted via the kidneys. The examination is associated with a low radiation exposure, which corresponds to about a third of the annual natural radiation exposure in Germany. The radiation exposure can be further reduced by emptying the bladder after the examination.

● cystoscopy

If bladder endometriosis is suspected, a urologist or sometimes a gynecologist can do a cystoscopy. The surface of the bladder wall can be assessed from the inside, but not seen through the different layers of the bladder wall. If the bladder wall bulges inwards due to the penetration of endometriosis into the wall, a tissue sample may be taken to confirm the diagnosis. Removal of the endometriosis through the bladder does not make sense, however, since the endometriosis cannot be completely removed through this access. A cystoscopy is also done if the ureters need to be splinted. This is useful, for example, in the case of ureter or kidney congestion under certain circumstances, as well as before extensive operations in the area

the ureter.

● MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a sectional imaging without x‑rays or radioactive rays. With the help of a strong magnetic field and radio waves, very precise images of the inside of the body can be created. Within the pelvis there is no additional benefit from MRI to transvaginal ultrasound in the hand of a trained person. Outside the pelvis, however, MRI is superior to all other non-invasive examinations, so that if atypical or very pronounced endometriosis is suspected, an MRI should be considered for better therapy and surgical planning.

Computed tomography (CT) does not play a role in the diagnosis of endometriosis.

● Presentation of the fertility center

If you have been trying to become pregnant for more than a year without success, you should introduce yourself to a fertility center with your partner. There, further examinations of your hormones as well as examinations of your partner will be carried out (e.g. checking the semen quality (spermiogram). A common timetable and arrangements with you between your doctor and your fertility center are essential. For example, an operation to rule out endometriosis should only be carried out if male causes of sterility have been ruled out.

● If necessary, other disciplines (gastroenterology, general surgery, ENT, …)

Depending on the complaints, it may be useful to include other disciplines in the diagnosis. Under certain circumstances it can be useful e.g. food intolerance or chronic inflammatory bowel disease

to be excluded before further diagnostic or therapeutic steps are initiated.

Therapy pillar 1: multimodal therapy

Endometriosis is understood as a chronic disease, so that we discuss the various options of multimodal therapy, hormonal therapy and / or surgery and work together to develop an individual therapy concept that is adapted to the respective life situation.

We will introduce you to the pillars of treatment in more detail below.

Pillar 1: The multimodal therapy

By the term “multimodal therapy concept” we mean a multitude of supportive measures that counter your monthly pain on different levels. In some cases, there is no scientific evidence (no scientific evidence) that the method helps. Nevertheless, in this case the principle “he who heals is right” applies. That means: if a method helps you, you don’t need scientific proof of it.

The multimodal therapy concept should accompany you in any case — regardless of whether you decide with your doctor for conservative or surgical therapy. Some methods of therapy are presented below. It is then up to you to try them out and find out for yourself what helps you. This path can be very individual and varies from patient to patient. This can also take some patience and self-discipline at times. Sometimes it is not that easy to find what helps you the most among all the offers. Perhaps rehabilitation treatment (“rehab” for short) is then suitable for you, during which you will get to know various therapy options.

Medicinal pain therapy

While hormonal or surgical therapy is aimed at combating endometriosis itself, the aim of drug pain therapy is to combat the pain caused by endometriosis. This is important because the human body has what is known as a “pain memory”. This means that if the pain persists, the body will send pain signals to the brain at some point even if the pain stimulus is no longer present. One then speaks of chronic pain. It also happens that the body perceives long-standing pain even more intensely. In the process, the painful area of the body is enlarged and a simple touch can be painful in the sensitized area.

For this reason, it is recommended not to bravely endure pain, but to counter it with suitable painkillers. Suitable here means that the amount and dosage must not exceed a certain level and only drugs that have a complementary effect should be combined. If the usual painkillers available in the pharmacy without a prescription in the approved doses do not help you adequately in some situations, a stronger, prescription drug may be indicated. Talk to your treating doctors about it. In some situations it can also be useful to present yourself to a pain center in order to receive an individual therapy plan there.

Diet change / nutritional advice

First of all, it should be emphasized that there is still no scientific evidence for the effectiveness of a certain “endometriosis diet” in the field of nutrition. Some studies also contradict each other and so can

no general or absolute recommendation can be made. However, many women report that a diet change tailored to them has done them good.

In particular, endometriosis-associated intestinal complaints (the so-called endo-belly) can be alleviated with the right diet. In this regard, it can help to reduce gluten and sugar as well as dairy products or to try to omit these foods altogether. Probiotics can also help support the intestinal flora and reduce intestinal problems.

The few studies that are now available regarding a link between diet and endometriosis risk suggest that consuming plenty of fresh (preferably green) vegetables, omega‑3 fatty acids, soy products, and dairy products that are high in calcium and vitamin D reduce the risk . In contrast, saturated fat, red meat, and alcohol seem to increase the risk of endometriosis. There are contradicting data regarding fruit and coffee, so that no clear recommendation can be made in this regard. There are also studies that have shown that antioxidant vitamins (vitamins A, C and E), vitamin B, as well as zinc and folic acid appear to reduce the risk. High-dose vitamin D has also been shown in studies to have a beneficial effect on endometriosis. In one study, substituting fish oil also reduced the risk of endometriosis. The fact that green tea extract has a reducing effect on endometrial lesions has so far only been shown in animal experiments, but it can be used on a trial basis.

Some patients react to the ingestion of histamine-containing foods with increased intestinal discomfort or even increased pain; here, too, it is worth researching whether there is a connection here.

It is important for yourself to find out what is good for you and what foods are making the symptoms worse. Here it is advisable to keep a “complaint diary” and to record exactly what you do and when

eaten and how you felt that day. If you give it a try and want to eliminate certain foods from the menu entirely, it makes sense not to omit several foods at once. If you feel better, it is sometimes unclear which food to leave out

the improvement is due.

Stay curious about your individual path and try to change your diet step by step. And if your cravings are too big, treat yourself to your favorite dish with pleasure. It does not help if the enjoyment of eating and thus the quality of life decrease due to remorse.

However, the women’s experience shows how much influence can be exerted (report Anna Lena Wilken with her book: As a rule, I am strong). That is why we consider this topic to be very important and are currently in the process of launching research projects in this area as well.

Mental Wellbeing — Psychosomatic Imagination or

Psychotherapy

Studies have shown that the mental state can have a great influence on the perception of pain. So we know that people with depression have a significantly increased pain perception. On the other hand, in the case of endometriosis, the disease itself can lead to depressive moods. If patients walk from doctor to doctor for many years without being helped or their social life is impaired as a result of the pain, psychological distress is often a typical side effect or even becomes the leading symptom. We were able to confirm this with our previous patients. In a master’s thesis by a psychology student, we were able to prove that the longer the pain duration, the greater the risk of depression. To break this vicious circle, psychosomatic or psychological therapy can be useful. This can also help to accept that one suffers from a chronic illness and to develop coping strategies.

The mental health of our patients is very important to us, so we are very happy that we can offer a comprehensive research project at the Charité; if necessary, the doctor will speak to you about participating in the study.

For example, we would like to investigate the connection between hormone intake and the occurrence of depression, but on the other hand we would also like to conduct structured interviews in order to gain better knowledge of the respective situation. There is definitely too little research here, we want to change that.

It is also important to mention that there are many patients whose relationships are burdened by their chronic illness. Sex life can also be impaired by the pain that is typical of endometriosis during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia). So don’t be afraid to consider sex or couples therapy. Here, too, we have a very empathetic colleague who is there for you and your partner (if you are interested, ask for an appointment with Ms. Nicole Gehrmann, gynecologist and sex therapist at the Charité women’s clinic).

Physiotherapy, exercise and sports

aThe fact that physical activity and sport have a positive effect on the body and soul has been well researched. As already described above, the psyche has an important influence on how we perceive pain. So-called endorphins are released during physical activity and lift the mood — an endogenous method to increase psychological well-being. In the case of chronic pain, those affected often take a gentle posture, which in turn independently strengthens the pain circulation. In endometriosis patients, this relieving posture and tension often affects the pelvic floor. Physical exercise helps prevent or relieve cramps. At the same time, muscles are built up, stress relieved and the immune system strengthened — this also increases well-being. It is now up to you to find out which sport is good for you and which should be integrated permanently into your everyday life. In addition to muscle building, targeted pelvic floor relaxation is also important.

Yoga or Pilates helps many women, but aqua sports, running or hiking in the fresh air are also recommended. Many also benefit from pelvic floor exercises.

Physiotherapy can also be very helpful for special problems or questions. In addition to exercises for strengthening, stretching and releasing cramps, the technique of transcutaneous electro-nerve stimulation with biofeedback (TENS) is available. Low-frequency current impulses are used here, which are intended to reduce the sensitivity to pain. Some health insurers take on this therapy — even if conclusive scientific proof of its effectiveness is (still) lacking.

Complementary treatments — osteopathy and traditional

chinese therapy with acupuncture.

Some patients have good experiences with TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine) and its important pillar of acupuncture. Even if there is often a lack of scientific evidence of effectiveness, these therapies can support and accompany the medical treatment approach. It is important to find a therapist to whom you can feel good access and feel comfortable.

Osteopathy

Persistent pain often leads to poor posture of the entire musculoskeletal system. Therefore a holistic treatment is necessary here. In our eyes, osteopathy is an important aspect, because specific manual treatment releases muscles and fasciae again, thereby relieving misalignments — especially of the ileosacral joint. At the same time, the upper shoulder girdle and diaphragm can also be affected. Some health insurers make additional payments here, so this form of treatment should definitely be integrated.

Stress reduction and “home remedies”

As described above, mental wellbeing is an important approach to leading a happy life with and despite endometriosis. Taking care of yourself and taking time for yourself are steps that are a key to more inner balance, even without endometriosis. Even if stress can never be completely avoided in our packed everyday life, one should consciously take time out and reduce stress as much as possible.

Well-known “home remedies” that many patients already use on a regular basis can also be helpful against pain. By applying heat to the painful areas or taking a warm bath in the tub, many women experience noticeable relief from acute complaints. With them, warmth has a relaxing, calming and antispasmodic effect. Meditation, autogenic training or progressive muscle relaxation can also have this effect.

Therapy pillar 2: operative therapy

In our center we have already cared for more than 15,000 endometriosis patients according to our philosophy and experience. As already described in the diagnostic section, no operation for pure diagnosis needs to be performed, but it can of course also be useful in individual cases and must be discussed individually. For example, in some countries, histological confirmation of endometriosis is mandatory before fertility treatment can be initiated (Austria). Or on your part there is a desire for a definitive clarification. The diagnosis of a relevant endometriosis can usually be made through an experienced examination solely through the analysis of your symptoms and the clinical examination.

If there is no current desire to have children and there is no evidence of organ destruction, conservative hormonal therapy can be carried out first; if the symptoms persist, one can wait and see. However, if the symptoms persist under hormonal therapy, then peritoneum foci are likely and surgical removal of these makes sense. For this decision, however, it is important to have been bleeding-free for at least 3 months under hormonal therapy; if you had bleeding under hormonal therapy, this is usually associated with symptoms, then that is it

understandable because this pain is caused by the uterus.

Your doctor should recommend surgery if:

- the clinical examination shows evidence of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with severe symptoms or the risk of permanent organ damage. An example of this is a congestion of the ureters or kidneys. This can occur on one or both sides and causes the kidney to lose its function over a long period of time.

- Conservative (non-surgical) therapy has not led to sufficient symptom improvement.

- On your part, there is an urgent need for histological confirmation of the diagnosis. However, the diagnosis of a relevant endometriosis is usually only possible through the analysis of yours

Complaints and the clinical examination and does not require any histological confirmation. - You have not become pregnant for more than a year despite having regular sexual intercourse. However, before taking any further steps, you should first be presented to a fertility center, in particular to rule out male causes of sterility.

What about pain relief? Isn’t that also an indication for surgery? Yes, of course, but a holistic concept should be pursued; This means, among other things, as few operations as possible and if operations, then as effectively as possible. Unfortunately, because the pain associated with endometriosis is complex, surgery cannot always remove all pain. In the past, a lack of analysis of the complaints and pain has led to many women having multiple operations, some of which were unsuccessful. The reasons for an operation must therefore be carefully considered. It should be noted at this point that only about half of the patients are symptom-free after surgical endometriosis removal.

For women who have not yet completed family planning, the top priority is organ preservation. This explains, however, that not all endometrial foci can always be completely removed, e.g. if the uterus itself is affected (adenomyosis uteri) or if the ovaries are affected. This can therefore continue to be the cause of pain.

In addition, recurring pain can lead to chronic pain over a longer period of time, which can lead to secondary pelvic floor changes and must be treated with multimodal therapy

should be. Further operations tend to lead to a worsening of the pain.

If endometrial foci are in the area of the uterus, some women with very severe symptoms consider an operation to remove the uterus (hysterectomy). The foci that are adjacent to the uterus can also be removed. Women usually only consider hysterectomy if the endometriosis has severely restricted their lives, other treatments have not been successful, and they are sure that they no longer want to have a child. A woman’s age also plays an important role in determining whether or not to have the uterus removed. In addition, an operation only makes sense if the results of the examination actually suggest an improvement in the symptoms. Usually, when the uterus is removed, the ovaries are left in place in order to keep the hormones produced.

However, hysterectomy alone does not guarantee that the endometriosis will be cured afterwards. As long as the ovaries are still functionally active and producing estrogen, endometrial foci in other locations continue to be stimulated and can cause discomfort. Removing the ovaries stops the production of female sex hormones (artificial menopause), thereby stimulating the endometrial foci. After this operation, some women have such severe general symptoms due to the discontinuation of the hormones that they want hormone treatment with estrogen. Then it may be that the hormone preparations trigger endometriosis symptoms again. Removal of the ovaries is therefore generally considered from the age of 45 at the earliest, also in order to keep possible long-term side effects (increased risk of osteoporosis, increased risk of heart attacks) as low as possible.

OP time

Regarding the time of operation in the cycle, there is no completely uniform recommendation.

If you are currently taking hormonal therapy, we recommend pausing it and only performing the operation after at least two menstrual periods. According to Köhler et al. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19819448) the hormonal therapy results in downstaging and inactivation of the endometrial foci, which can no longer be seen so clearly during the operation and can therefore be overlooked more often the operation may not be a complete removal of the endometriosis.

In the case of a clarification about the desire to have children, we also recommend performing the operation between the 1st and 10th day of the cycle, especially if the operation is combined with a diagnostic uterine specimen and a patency check of the fallopian tubes (chromopertubation). At this point, the visibility in the uterus is better if the mucous membrane is only slightly built up. In addition, a pregnancy may theoretically have occurred in the second half of the cycle after ovulation, which is not yet detected by a regular urine pregnancy test.

In the case of endometriosis renovations, this can also be deviated from, since endometriosis foci can be displayed particularly well, especially shortly before the bleeding, both in the uterine specimen and in the laparoscopic examination.

Preparation for surgery

If the joint decision on an operation has been made and an appointment has been made, further preparatory measures must be carried out beforehand. This includes the operation briefing, in which your doctor explains the general procedure of the operation and both the general and specific risks.

How exactly does the procedure work? Can there be side effects or complications? The operating doctor will clarify these and other important questions with you in an initial discussion. Aftercare and rehab are also discussed.

The anesthetist will then provide information. The various forms of anesthesia, their process and risks and, if necessary, special pain therapies are discussed. Depending on the previous illnesses or previous operations, the anesthetist recommends further examinations, for example to ensure the functionality of the heart and lungs.

When a blood sample is taken, not only the regular blood count, but also kidney values and coagulation are checked. The value CA 125 is not suitable as an activity marker for endometriosis, as this is a non-specific value, which is increased in diseases of the peritoneum or ovary, including peritonitis or ovarian diseases.

If an operation involving the bowel is planned, your doctor will give you recommendations on laxative measures before the operation. It should be emphasized here that if a complex endometriosis operation is planned even with partial bowel resection, it is advisable to consider local pain therapy (epidural anesthesia) for postoperative pain control. Painkillers can then be given on top of it and we have to give less all over the body, which in turn has side effects. This may sound a bit scary at first, but it is usually a great advantage and is also recommended by us gynecologists.

We ask you to pay special attention to your personal hygiene on the day or in the morning before the operation, including cleaning the navel, especially if you have a laparoscopy.

OP process

For a planned operation, it is advisable to be sober. This means that at least six hours should have elapsed between the last time you had food and drink and the operation. This also includes chewing gum and smoking. Clear drinks such as water or tea without additives are possible in small quantities up to two hours before an operation. These strict rules serve to protect you from so-called aspiration pneumonia! The stomach contents with stomach acid run up the esophagus into the lungs and can lead to severe pneumonia there. In the case of planned, so-called elective interventions, we do not want to take this risk for you and insist on the fasting times mentioned above.

After you have been called by the OR team, you will be brought to the OR by the nursing staff or a service team. The anesthetist will usually meet you there. Depending on the activity, your doctor will try again to answer any questions you may have.

An endometriosis operation is usually carried out by laparoscopy, ie. Minimally invasive. Endometriosis sanitation can take from 20 minutes to several hours, depending on the extent. With a laparoscopy, one usually goes into the abdomen via the navel and then pumps carbon dioxide into the abdomen so that the abdominal wall is lifted from the organs and the working trocar sleeves can then be inserted into the necessary positions in the lower abdomen with significantly reduced risk. Usually these are two to three approx. 1 cm long incisions on the left, center and right in the lower abdomen. If you have already had several previous operations, it may be a safe option to insert the first trocar on the left side below the costal arch in order to insert the camera from there and remove any adhesions from previous operations in the area of the navel under sight and then carry out the operations as usual .

During a laparoscopy, all abdominal organs are shown, including the diaphragm, liver, spleen, stomach, intestines and appendix. Only then do you inspect the female organs in the pelvis. During a laparoscopy, photo documentation can usually be provided so that the findings and surgical steps can be demonstrated to you after an operation.

Very rarely, usually only in an emergency situation, it is necessary to operate through an abdominal incision for endometriosis rehabilitation. This can then be done either across the lower abdomen over approx. 10 cm or lengthways from the pubic bone to the navel, very rarely beyond.

If part of the intestine has to be removed, the affected part is usually cut out and the healthy ends sewn back together (anastomosis). Most intestinal endometriosis lie in the area of the rectum, which has a reservoir function until the stimulus to defecate occurs. This intestinal area must therefore be able to tolerate large changes in volume. A suture in partial resections in the area of the rectum is therefore exposed to extremely high stresses due to recurring stretching of the intestinal wall. Therefore it can sometimes be necessary to create a (temporary) artificial anus. A piece of the small intestine is sewn to the abdominal wall so that the stool contents can flow away well above the suture in the rectum. In this way, the anastomosis can heal in peace without stretching stimuli and the artificial anus can be moved back after a few weeks. A permanent artificial anus is only very rarely required.

If endometrial foci occur in the area outside the small pelvis during the operation, your doctor may call in surgeons from other specialist departments for the operation so that the general surgeon may be involved in the bowel or the urologist may operate on endometriosis of the ureter. However, depending on the training of your gynecologist, simpler interventions can also be carried out without the help of other specialist departments.

Objectives of the operation:

- Confirmation of the diagnosis (through histological analysis)

- Determination of the spread of endometriosis

- Reduction of complaints through maximum endometriosis rehabilitation, possibly with remaining findings depending on the agreement made before the operation (uterus with adenomyosis uteri and incomplete family planning, slight intestinal involvement without complaints to avoid bowel surgery, …)

After the operation

After the operation you will first spend a few hours in the recovery room, where you will be asked whether you are in pain and will be given additional pain medication if necessary. Normally, you will be transferred from the recovery room to the normal hospital ward, where you will continue to be looked after. Depending on the time of the operation and the rest of the operation program of the day, your doctor will talk to you about your findings and the course of the operations on the day of the operation or the following day at the latest. In addition, will your doctor be able to give you individualized recommendations on how to proceed?

Checklist questions to ask my doctor:

● Do I even have endometriosis?

● How widespread was my disease?

● What other treatment options can I consider?

● What are their advantages or disadvantages?

● Would you recommend further treatments?

● Am I entitled to follow-up treatment (AHB)?

● When should I next introduce myself to you?

Depending on the extent of the operation, you will spend between 1 and 5 nights in the hospital after the operation. The urinary catheter can usually be removed after getting up for the first time, occasionally in the evening of the operation, usually the next morning. If a partial bladder resection was performed during your operation, the catheter usually has to remain in place for 7 to 10 days so that the bladder wound can heal undisturbed.

Since the nerve plexuses of the bladder are occasionally shown during the operation, we check whether they can urinate well after the operation. This can sometimes lead to disruptions, so that special training is required here. It is then necessary to keep calm, the nerve supply is usually only irritated and needs a few days to a few weeks to regenerate. To do this, we usually insert a urinary catheter again, and occasionally we support this phase with special medication.

During the inpatient stay, the social services should introduce themselves to you to talk to you about rehabilitation measures or follow-up treatment. There are certain institutions that specialize in endometriosis. You are welcome to refer to the

website of the German Endometriosis Association before the interview.

Therapy pillar 3: drug therapy

Treatment with medication is primarily aimed at relieving or eliminating severe pain or cramping associated with menstruation. Painkillers and hormonal agents that suppress ovulation (hormonal downregulation) are available for this purpose. In the case of recurring but not extremely stressful abdominal complaints, painkillers or gestagens in the form of mono- or combined preparations can provide noticeable relief. These preparations are often very well tolerated and are therefore usually also suitable for young women with endometriosis. If they don’t bring enough relief, stronger medications are an option.

Painkiller

Painkillers from the group of so-called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often used to treat menstrual symptoms, but also for endometriosis. These reduce the freeing of

pain messengers. These include, for example, the active ingredients ibuprofen, diclofenac and paracetamol. Some of these drugs are available over-the-counter, others are only available on prescription in higher doses. Novlagin and Metamizol are also suitable.

NSAIDs can effectively relieve severe menstrual pain and are usually well tolerated as long as the pain is acute. At first, clinical experience shows that they can help with period pain quite effectively. But there are few studies that investigate its effectiveness for other pain caused by endometriosis. These drugs can cause side effects such as stomach upset, nausea, and headache. Without medical advice, painkillers should therefore not be taken frequently or for a long time.

Over time, however, these drugs can lose their effectiveness, women have to take more and more painkillers, and this is where chronification mechanisms come into play or a progression of the endometrial lesions.

Period pain that cannot be treated well with 1–2 ibuprofen 600 mg, so that there is no inability to work and / or bedridden, should be further clarified.

Some colleagues recommend so-called opioids to treat severe pain. These remedies imitate the effects of the body’s own pain-relieving substances and influence how pain is felt in the brain. Opioids may only be used if prescribed by a doctor. Especially with the more effective opioids, there is a risk of dependence with prolonged use. Side effects such as nausea and vomiting, constipation, tiredness, dizziness and fluctuations in blood pressure can occur. No reliable data are available yet on the effect of these painkillers in endometriosis and are not indicated unless this is done under the care of very experienced endometriosis specialists and pain therapists

is taken.

Hormonal treatments

Hormonal active ingredients suppress the body’s own hormone production in the ovaries and thus also ovulation and menstrual bleeding. They are not suitable for women trying to get pregnant.

It is important to us that you understand the processes in the hormonal cycle in order to understand the effect of the body’s own hormone production on endometriosis and also the effect of hormone therapy on endometriosis. It is important that you make your own personal opinion with regard to the risk / benefit assessment

can. We are concerned with your quality of life, taking into account the aspects of untreated endometriosis.

A current trend is that hormones have more disadvantages than advantages and this may well be justified for women without hormone-dependent diseases such as endometriosis. In case of a

endometriosis treatment there is a medical indication.

We have the problem that:

- Untreated endometriosis pain is often extremely severe, which can hardly be managed with multimodal therapies and, if these are treated ineffectively, more and more lead to chronic pain, which in turn causes secondary changes such as pelvic floor dysfunction and increasing pelvic pain, such as pain during intercourse, urination and defecation

- Endometriosis can progress during the normal cycle; if organs are not yet damaged, this can be associated with possible damage to fertility over the course of years

- Even after endometriosis has been surgically removed, this disease has a strong tendency to recur (10% / year for peritoneum foci; 30% for cysts); this is also significantly reduced when hormonal is initiated

Long-term therapy, especially important if there were cysts and an operation has already been carried out on the ovary. Further damage to organs due to the occurrence of new cysts should be avoided here,

until the desire to have children could be implemented. Too little attention is paid to this, even after a single operation on the ovary there can be irreparable damage. Or a developing adenomyosis can strongly influence the chances of pregnancy and also the pregnancy complications.

From our point of view, these are unfortunately serious reasons to treat endometriosis.

On the other hand, there are side effects

Many women complain of spotting, especially with the well-known progestogen-only preparation “Dienogest”. These are often associated with pain. This is not in itself a side effect, but an ineffective effect, because then your ovaries are stronger than the progestin. They cannot be “put to sleep”, so to speak, and the hormonal downregulation is inadequate, the ovary is active, forms follicles which then also form estrogens, the mucous membrane in the uterus builds up a little and there is bleeding. This can be seen by using the ultrasound to look for functional signs on the ovaries and the thickness of the mucous membrane in the uterus. In this case it makes sense to increase the dose (1–0‑1), or if the bleeding does not stop after 7 days, take a break of 7 days so that the mucous membrane can bleed off. Then it starts again. If this is the case, it is understandably not nice and also not useful and so not medically considered. So the longer you try, the more likely this bleeding will stop. Ultimately, the goal is to be bleeding-free. The effectiveness of the drug on endometriosis can only be checked if one is bleeding-free.

Now we come to the real side effects, these can be progestin-related side effects, we all know how we feel before our days, even if the natural progestin predominates in the body: impure skin, mood swings up to depression, water retention, breast jokes, you have to weigh up for yourself, you shouldn’t stop taking the medication too hastily, this usually ends after 3–4 months for many patients. If the side effects outweigh the benefits, we can look for other gestagens that are better tolerated. In Germany only the “Dienogest” is approved for the treatment of endometriosis, which means that it is paid for by the health insurance company, others are not and are then available as off-label use.

In principle, you can also take combined preparations such as the pill, which then try ethinylestradiol and dienogest (in the same dosage as dienogest mono). Here, the tolerance is in some cases significantly better, but on the other hand there is the estrogen content in the preparation, which we do not really know in the long term whether it also has a growth effect on endometriosis cells. Therefore, progestin monotherapy is currently to be regarded as the first choice when initiating hormone therapy and then other preparations as the second choice.

Most important to us, however, is your quality of life. So if hormones (systemically, i.e. as a tablet) are not tolerated, it is difficult, but there are ways here too. That must then be clarified individually. But first of all it is important that you understand the principle and thus find your own attitude towards it.

Then you can, for example, consider a local hormonal therapy with a progestin-containing IUD (LNG IUD). This is placed in the uterus. It releases the hormone locally, it only passes into the blood to a very small extent (it can be detected in the blood, but the concentration is not high enough to influence the cycle, i.e. the cycle persists). Many women who suffer from systemic hormonal therapies, especially depression, cope much better with the IUD. Exceptions prove the rule, but it’s definitely worth a try !!!

The available studies on endometriosis are limited. The LnG-containing IUD is approved for the presence of hypermenorrhea (very heavy menstrual bleeding) and this is what many women with adenomyosis uteri have and therefore this can also bring about a very good improvement in this regard. The effect is mainly local, so menstrual pain is often much better, so it has little or no effect on severe endometriosis in the abdominal cavity.

The LNG coil is also used as a contraceptive; Possible side effects such as intermenstrual bleeding, pelvic problems, acne and breast tenderness are known from this application. This shows that it passes into the blood to a small extent and that hormone-sensitive women in particular can react, but as I said, it is worth a try.

It is rare that the ovaries simply cannot be downregulated; then, in the case of severe pain, there is only the option of central downregulation with GnRh analogues (artificial menopause). That sounds terrible too, but unfortunately it is still an effective therapy in such situations. The drug itself does not actually have any side effects, it is a replica of the body’s own hormone. The administration (syringe) continuously stimulates the receptors and then the cycle comes to the switching point of the hypothalamus

succumb, so that then really no more stimulation from the brain can take place. The side effects are basically what we want to achieve, namely a downregulation of the ovaries, which no longer make a sound. The

lack of estrogen leads to hot flashes, sleep and concentration disorders, all of which we can expect in the menopause, but not necessarily. It is the same with younger women, not all of them have such extreme side effects, that also depends on the fat store, for example, where estrogens are also formed. In order to counteract the side effects, an add-back replacement therapy is usually added, that is a small dose of estrogen / progesterone, so that the treatment is tolerable. Indeed there is

some patients who have experienced significant pain relief and only thus were able to control the pain and for whom long-term therapy is even possible. The most important thing here is also to consider bone density. Without add back HRT, GnRha may not be given for more than a total of 12 months. Therefore we use the add back therapy to counter possible effects on the bone.

Watch & Wait

Hormonal or surgical therapy does not always have to be initiated immediately if endometriosis is suspected or if it has already been histologically confirmed. It makes sense to wait and see if you are currently planning to have children but have not yet tried to become pregnant. While it is true that childlessness is an important issue in endometriosis. Nevertheless, almost half of endometriosis patients become pregnant spontaneously. Since there is usually no menstrual bleeding during pregnancy and also during the subsequent breastfeeding period, the symptoms are often significantly alleviated by pregnancy. So it makes perfect sense to try whether it works with the spontaneous pregnancy. If after a year, despite regular sexual intercourse (at least 2 per week), pregnancy has not occurred, an appointment at a fertility center is recommended and you should also talk to your doctor about endometriosis surgery. Even if you are only slightly distressed despite endometriosis, you do not need to act immediately. In this case, it may be sufficient to change one’s lifestyle in line with the multimodal therapy concept. If you and your attending physician decide on an observational concept, regular medical check-ups are indicated.

Re-introduction

Depending on the findings and the therapy that has been decided, a follow-up appointment will be arranged with you. Since endometriosis is a chronic condition, it will stay with you until your menopause occurs. How often your doctors will call you for follow-up checks depends on your stage of illness, the therapy chosen and your plans and ideas. It often makes sense to present yourself for a check-up after three months, when a new therapy concept has been established. In this way it can be found out whether the new therapy will help you or whether there are application problems, for example. A short-term re-presentation is also recommended after an operation and subsequent therapy. If, on the other hand, you have decided to attempt a spontaneous pregnancy, you may not need to see you again until it does not occur spontaneously.

So every time you visit, ask your doctor exactly when he or she would like to see you next and make an appointment as soon as possible.

Life and everyday life

Endometriosis is a disease that can affect many important areas of life — from self-esteem as a woman to partnership, family and life planning.

In order to find a way to get the best quality of life possible despite the symptoms, some decisions have to be made. Good information helps here — about the type of therapy and ways of organizing your own life so that the symptoms burden your everyday life as little as possible.

Good care and support from a doctor with extensive experience in the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis is important. Medical attendants should also be familiar with the physical and psychological stresses and social effects of the disease. It can be helpful to get a second opinion when making difficult decisions, such as for or against surgery.

In order to be able to deal with endometriosis and its possible consequences, good support from family, partner or friends is valuable. This presupposes that relatives are also informed about the disease and have an understanding of the burdens that it brings with it. For some women, the exchange with other affected persons in a self-help group also means important support. Others prefer to solve their problems for themselves. It is crucial that every woman finds her own way to deal

with the chronic disease